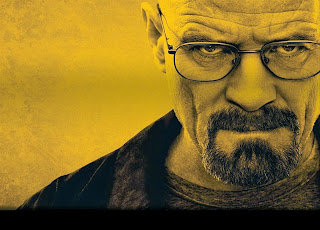

"I Did it for Me"

I can´t add much to what is zinging around the blogoshpere about "Breaking Bad." My family and I watched the entire series and avidly followed the story week to week. I often refer to "Breaking Bad" in academic presentations and university classes. I can´t think of a better example of character development (or character unraveling) and the writing, production and filmography is so superb. Some stray thoughts as I still come to grips with last night´s final episode:

1. Some bad decisions can be reversed with minimal inconvenience:

when you’re single you can vow never to go out with that White Supremacist kickboxer

again or swear you’ll never ask for the extra spice on the curry chicken at the

Thai restaurant. But some decisions are

so catastrophic and profound that you can never recover from them. Walt headed down the road of the meth-cooking

business and bullied Jesse into coming with him and before long, there was no

way to undo it. Almost nobody in the

whole series that got into the meth business came out alive.

2. To take a moral stance like Walt did, ostensibly providing

for his family by engaging in an activity that ruined the lives of thousands of

people, has a blowback effect that cannot always be calculated. Saying, in effect, “I’m going to take care of

me and mine and the rest of the world is not my problem,” may create such a

large problem that it eventually eats you up.

It’s not just what you do to other people outside your declared circle

of responsibility; it’s what you become that gets problematic. Breaking Bad may be a metaphor for American

foreign policy and big business and our own individual apathy toward the larger

impact of our small daily decisions.

3. One’s own declared intentions are slippery. Walt had us all believing he was cooking meth

solely to provide for his family after his demise. He probably even believed it himself. Then, he passed up chance after chance to get

out until it was too late. In the final

episode he admitted to Skyler, “I did it for me.” How many things do we do out of our own

self-interest and then try to dress it up as if our intentions were noble? How effectively can we really weigh the depth

and complexity of our own intentions?

4. Lies are damaging but lies between family members are

enormously destructive, resulting in lost trust, lost intimacy, lost support. Walt lied to his family so many times that

when he finally told the truth (that he didn’t kill Hank and actually tried to

buy his life with all the money he had left) they didn’t believe him. Maybe if you´re contemplating doing something so bad you don´t want to tell your family about it you should take that as a real solid clue not to do it.

5. Most of us don’t do what we do for money. We may want the money for the prestige, power,

security and leisure that comes with it, but the money ain’t the thing. Walt, beyond having a hot car and the ability

to buy one for his son, didn’t care about the money except to build an empire

to rival the legal one (Grey Matter, Inc.) he was forced out of by Elliott and

Gretchen. Jesse was eventually so

disgusted by how he came by his money he drove around and threw it out the

window in a poor neighborhood.

5. "Breaking Bad" should challenge our notions of who gets to be

classified as a decent person. Walt hid

in plain sight, as did Gus Fring, because he appeared to be an upstanding,

model citizen. Walt was beyond suspicion

when the lab equipment went missing out of his classroom and he let the poor

Native American janitor take the fall.

Jesse’s drug history and appearance marked him as an addict and a drug

dealer, making him the target of suspicion and abuse, but he turned out to be

infinitely more caring and moral than Walter White.

6. The series should make the viewer question (for at least an

hour on Sunday night) the benign appearance of the apparently quotidian: the

chicken restaurant, hay truck, the nerdy high school chemistry teacher, the car

wash, the Stevia packet, the industrial laundry and the stacks of canned cold

drinks being wheeled into a business on a dolly. For me it reflects the lethal, tainted, corrupted thought that

lurk beneath our language.

Meaningless, boilerplate expressions shield our insincere, feigned

interest in others. Questions about

someone’s job title are a thin veneer for our sexism and racism. So much of what we say and how we say it

cover up complex, deep seated values and opinions which, if we really examined

them, would shame us.

7. We want to dedicate ourselves to something that has profound

meaning, even if it´s really hard. At a couple

of points in the series Walter White said he felt most alive when he was cooking and

selling meth (which also meant he was close to death – see Freud’s Death

Drive). I don’t think we’ll shy away

from doing hard things when we’re given the freedom to exercise our talents and

initiative and we can see some positive (according to our definition of

positive) outcome.

8. There’s more to what makes us tick than what science can

figure out. In one flashback, Walt and

Gretchen (then his colleague) try to determine the

chemical composition of a human being. Despite

their best efforts to account for all the elements and reach 100%, there was

always a small fraction of a percentage they couldn’t account for. Gretchen asked, “Could it be the soul?” Walt dismissively answered that there was no

such thing. That was the brilliant

chemist’s biggest miscalculation. Yes,

we have a soul. Watching Walter White lose his in this fictional TV show gave me an opportunity to search mine.